Remembrance of Things Past

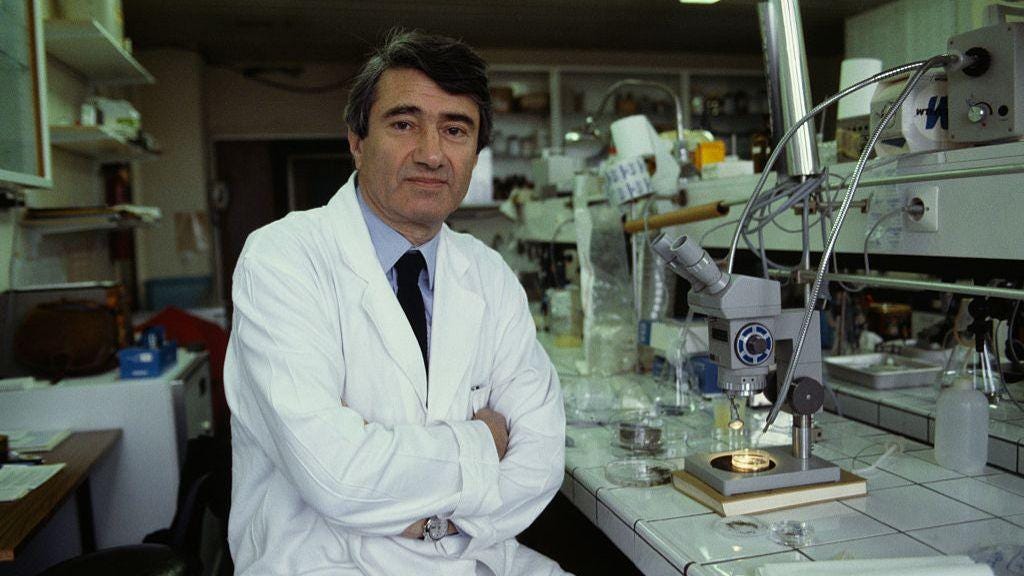

A look back at Dr. Etienne-Emile Baulieu, the inventor of the abortion pill RU-486, who died recently, and what women's magazines once were like.

Thirty years ago, I was assigned a 4,000-word reported feature for Self magazine about the abortion pill, RU-486. I was reminded of it when I heard the news last month that Dr. Etienne-Emile Baulieu, the inventor of RU-486, had died in Paris at the age of 98. I went to look for my story online, and couldn’t find it. I asked the American Library of Paris, with its vast research network, to do a search, and they couldn’t find it online either; it seems none of Self’s archive from 2000 back is available digitally. So I found my original unedited piece in my archive, and thought I’d post it here. (I’m listening to this as I write; seems like a good soundtrack.)

Today, that article would not be assigned, for a variety of reasons. First, of course, is political: The United States has become too divisive, especially on the topic of abortion, for a mainstream women’s magazine to publish such a piece. Second, the magazine business have been so gutted, no mainstream publication beyond The New Yorker, or maybe The Atlantic, would assign a 4,000-word story at $2 a word—the rate I was paid then; that is still the going rate, 30 years later, making doing this job almost impossible financially.

And, third, thanks to smartphones, where most everyone reads things now, and social media, which is all about scrolling, the attention span of readers is too short to take in a 4,000-word magazine story, at least on a screen. After reading this piece again, I have to say: I miss doing long, reported stories on serious subjects—stories for which I was given many months to research and write. Today, I’m lucky if I get a couple of weeks, and a thousand words. I also miss reading these sorts of articles.

It’s a different business now.

Happily, we have Substack, where I can write long-ish, on all sorts of subjects, without a pressing deadline.

Be forewarned—we now have to put trigger warnings, something that was not done by magazines in the 1990s: This story is graphic. I’m making it available for free, with the hope that some of you will take advantage of The Styles Files’ third anniversary discount on annual subscriptions, and help make serious, independent journalism financially viable.

A funny aside: Dr. Baulieu was known as a player, with a long list of mistresses, some of them reportedly quite famous. One of these lady friends, the movie star, called while I was interviewing him—he made sure I understood who was on the line. After he hung up the phone, he turned to me and asked me out to dinner. I declined, but was impressed at how coolly he was living up to his playboy reputation. I also found it ironic that such a Lothario was helping make unwanted pregnancies easier and safer to end. Did he invent RU-486 to help women? Or men? I leave you that to ponder.

Why France Has the Abortion Pill and We Don’t

By Dana Thomas for Self, 1994

Nadia feels lousy, really lousy. She’s sitting on one of the cushy green velour recliners in the dimly-lit lounge of the Broussais Hospital’s family planning center on rainy April morning in Paris, waiting to expel her fertilized egg.

“Have you ever thought about wanting your period all in one day?” she asks. “You know, all the cramps put together in one day? I’ll tell you, you want to keel over.” She’s already been sick to her stomach once.

In the early days of the French abortion pill, RU-486, women who took the compound, dubbed the “death pill” by some and a wonder drug by others, suffered from severe cramping, diarrhea, nausea and vomiting. But in the six years since the drug was approved and registered in France for pregnancy termination, the method has been adjusted, refined, polished, you could say. Unlike Nadia, most women who take RU-486 hardly have any pain at all.

When President Bill Clinton lifted the ban on the testing, licensing and manufacturing of RU-486, last January, it became clear that women in the United States would soon be offered what their counterparts in France, Sweden and the United Kingdom have had for a few years: A non-surgical, safer and inexpensive alternative to the aspiration abortion.

Of course, there were the many political problems that had to be worked out. The pill’s manufacturer, Roussel-Uclaf, refuses to sell RU-486 in the United States because of conservative political pressure, so an American licensee was needed.

Last April, the Federal Drug Agency announced that the Population Council, an international nonprofit research organization based in New York, would conduct clinical trials, find a manufacturer and distributor and file the New Drug Application. Testing is expected to begin by the end of the year, and it has been predicted that the pill will be available to the American market within two to three years, perhaps even as soon as next summer. [1994]

So why does the United States need an alternative to the aspiration abortion?

First, because it is 96 percent effective, says Dr. Etienne-Emile Baulieu, the inventor of RU-486, adding that it is “easy” and “cheap.”

Second, with the pill, he says, there is no invasion of the body, no chance for perforation of the uterus.

Third, says Dr. Elisabeth Aubeny, chief medical officer of the Broussais Hospital’s Centre d'Orthorgenie, explains that when a woman undergoes an aspiration abortion during the first few weeks of a pregnancy, the egg is so small and difficult to find that tissue may be left in the uterus, causing hemorrhaging and infection. This does not happen with RU-486.

And fourthly, the political reason: “In my opinion,” Baulieu says, “the future there will be no real need for abortion clinics, and therefore preferred targets of Pro-Life activists will not exist.”

Plus, there are many other potential applications for the drug, including: for therapeutic second and third trimester abortions, to induce labor, as a morning-after pill, as estrogen-free daily oral contraceptive, and as a treatment for breast cancer, meningiomas (brain tumors) and glaucoma.

Nadia, a 22-year-old French-American studying art history in Paris, chose RU-486 over aspiration because she thought it would be "less traumatic." She didn't like the idea of anesthesia, surgery, tools. She wanted to be in charge.

That is how most of the women who take RU-486 at the Broussais Hospital feel, reports Aubeny. “They say, ‘It involved me a lot, but I preferred it that way. It was my abortion and not the abortionist’s.’”

RU-486, or “mifepristone,” was devised in 1980 to disrupt progesterone during the reproductive cycle. Progesterone, a hormone found throughout the body, has several purposes in the reproduction process: it thickens the uterine lining before implantation of the fertilized egg, suppresses ovulation after fertilization and calms uterine contractions once the fertilized egg is in place.

When taken, the “anti-progesterone” RU-486 acts as a road block, jamming these messages transmitted by the progesterone, causing a breakdown of the between the egg and the uterine wall. The cervix dilates, the uterus contracts and eventually, the egg is expelled.

At first, RU-486 was given in one 600 mg. dose and proved to be 80 percent effective in ending pregnancies of six weeks or less. Researchers wanted to improve that figure, so prostaglandin was added to the equation. Prostaglandins are local-action hormones which cause contractions in the smooth muscles in the body, including those in the uterus. In fact, prostaglandins, when ingested, can induce abortion and prescriptions often carry labels warning that the product can cause miscarriages. In some countries where abortion is illegal, such as Brazil, women take oral prostaglandins to begin an abortion then go to the hospital where doctors must complete the procedure with aspiration.

Two prostaglandins were chosen: gemeprost, administered by suppository, and sulprostone, given by injection. Patients received one of the two prostaglandins approximately 48 hours after taking the RU-486. The procedure was 96 percent effective, with expulsion taking place in four to five hours. Those who do not expel undergo aspiration to finish the abortion.

Unfortunately, the side-effects of the prostaglandins were rather harsh: severe cramps, nausea, diarrhea, vomiting and sometimes, because of the smooth-muscle contractions, changes in arterial pressure and cardiac function. To reduce these side-effects, the amount of prostaglandin administered was gradually reduced.

In 1991, Baulieu and Aubeny decided to experiment with oral prostaglandins as a potential replacement of the injections and suppositories. Baulieu’s objective was not to make the procedure safer, more effective or less painless—although all three are direct results of the experiment. Instead, Baulieu wanted to make the procedure as private as possible: women can undergo an RU-486 abortion in their doctors’ offices, or “even stay at home and have the doctor visit them and...take RU 486 when they decide,” he says. By doing this, Baulieu believes that public protests by pro-life activists will virtually disappear. There will no longer be the need for abortion clinics, therefore, no sites for public intimidation and aggression.

Through testing, Baulieu and Aubeny discovered that taking prostaglandin orally was “much smoother” than when administered by injection. “If you measure the prostaglandin intake after a shot, it’s whooosh, up,” he says. Sometimes this caused “cardiac accidents.” Three patients suffered heart attacks and a fourth died—a 31-year-old women who smoked two packs of cigarettes a day and was in her 13th pregnancy. “She was really a sick person,” Baulieu says now. “She was a medical mistake.”

The Health Ministry officials immediately ordered family planning centers to cut the dosage of sulprostone in half, banned treatment for women who are regular smokers and over the age of 35, and called for research on the use of an oral prostaglandin.

Dr. Ian Mackenzie of the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford, England believes that the over-35-smoker rule, which is also used in the United Kingdom, is not really necessary, concurring with Baulieu that the reason that woman died was because she was “a medical mistake.”

“Yes, there are risks” for those who are over 35 and are heavy smokers, he says, “but the risks may be greater having a surgical abortion rather than a medical procedure.”

Baulieu had tested several different types of oral prostaglandins when he heard about misoprostol (commercially known as Cytotec), a medicine prescribed to treat ulcers and known to cause spontaneous miscarriages. Baulieu was surprised to find that when he told Roussel-Uclaf of his intentions of mating Cytotec with RU-486, the pharmaceutical company executives balked, fearing that using Cytotec for abortions would put the company “on bad terms” with the drug's manufacturer, G.D. Searle, of Skokie, Ill. Ironically, Searle was the first company to manufacture and distribute the birth control pill 30 years ago.

Roussel-Uclaf refused to cover insurance costs for clinical trials of Cytotec with RU-486. However, since Baulieu is the director of the government-run Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, he was able to secure government research funds, and he conducted his trials. The day he announced his discovery publicly in a speech at the Academy of Sciences in Paris, he was told about the woman who died after receiving the prostaglandin injection.

Now, two years later, the combination of RU-486 with the oral prostaglandin is the only method used in France. In a recent study requested by the French government, 500 women were tested for the effectiveness of the RU-486 combined with prostaglandin. Twenty percent suffered from no pain and expelled easily, sixty percent had mild contractions, similar to regular menstrual cramps, and 20 percent had cramps which required pain killers, and the method proved to be 96 percent effective.

Injectable prostaglandin is still used widely in England because oral prostaglandins have not been licensed for this application. Last winter, [1993] the Wall Street Journal published a letter from G.D. Searle disavowing the use of Cytotec with RU-486 for abortions.

“Searle has never willingly made misoprostol [Cytotec] available for use in abortion nor is it the company's intention to do so,” wrote Charles Fry, corporate vice president for public affairs. However, Searle did revise its Cytotec labeling in France, at the behest of the French ministry of health, to include “limited” use for abortion “in specialized hospitals.”

“It’s a very life-saving product,” says company spokesman Jeff Newton, of Cytotec. “And that seems to have gotten overlooked.”

Either way, Dr. David Grimes, chief of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of California, San Francisco, says that the medical community does not need permission by Searle to use Cytotec for this purpose.

“Once a drug is approved,” says Grimes, “we can use it however we want.”

Four of out of the seven women who come to the Hospital Broussais in southwest Paris each day for an abortion choose RU-486 over aspiration. Most opt for the pills because they want to avoid the surgical intervention, and because they feel more in control.

Critics of the method in the United States claim that taking the pill is easier psychologically than aspiration, thereby making abortion a more attractive response to an unplanned pregnancy. The numbers disprove this: since the pill was introduced in 1987, the abortion rate has dropped or remained the same in France. And the women will tell you that this presumption is absolutely not true.

“When I did this 15 days ago my first reaction was, ‘It’s great,’” says 26-year-old Monica, who is back at Broussais for her two-week post-abortion check-up. “But when I left here, I felt really bad, because with [aspiration], you sleep, so you don’t see anything, and with this, you have to sit and wait. For three hours you are sitting and you're waiting for it.” (Unlike in the United States, women in other countries are often put under general anesthesia for an aspiration abortion).

This is Monica’s fifth pregnancy and third abortion—she had undergone two aspirations in her homeland Brazil when she was 17, and now has two daughters, ages three and nine months, with her French husband of four years. There was no way they could afford to support another child on his small salary as an assistant in video production. She even recently got a job waiting tables part time to help pay the bills they have with two. They want to have a third child, she says, they just can't now.

Her gynecologist sent her to the Broussais Hospital, one of the nearly 800 public health centers and clinics that conduct RU-486 abortions. Like everyone who comes there, she was given the option of RU-486 or aspiration. Both run about the same price—about $270—and 70 percent is picked up the national health care plan. It is purely a decision of pills versus instruments. Since she had undergone surgery twice, she opted for the pills.

The pills are an attractive option for the American medical community as well. The number of doctors trained in the United States to perform abortions has dropped significantly in recent years, and in rural areas of the country, access to abortion clinics is increasingly limited.

“It’s a real problem now,” Grimes says. “We, in academics, have really dropped the ball” when it comes to teaching the procedure to medical students. “RU-486 is much different. The cervix is already dilated, soft and open. The abortion could be completed with a syringe. It’s very low-tech medicine.”

The Veil Law of 1975, put forth by France’s health minister at the time Simone Veil, and which made abortion legal in France, states that every woman who wants to terminate a pregnancy must wait eight days from the time she has her initial examination until the abortion, “for reflection.” Following this period, she must speak to a social worker at the hospital to make sure she is comfortable with her decision. Only she has done this, she may have the abortion.

Monica sat down with one of the nurses, read all the papers that state that she accepts full responsibility for the interruption of her abortion and that she will follow all of the medical rules for the procedure. Once she signed them, she was given three 200 mg pills of RU-486, which she quickly swallowed with a cup of water. Then she was sent home.

She quit smoking for 48 hours—one of the strict guidelines for RU-486. Women who smoke no more than ten cigarettes a day can use this method, but they must stop smoking during the two-day period between the ingestion of RU-486 and the prostaglandin.

However, those with respiratory problems, liver or kidney problems, asthma, uneven heartbeat, diabetes, glaucoma, those who have had a Caesarian section in the last year or currently receiving cortisone treatments or those over 35 and heavy smokers (more than ten cigarettes a day) may not use RU-486.

“We have to be cautious,” Aubeny says. “Very cautious. We know if there is ever a major problem, it would finish the RU forever.”

Two days later, Monica came back to the hospital at 8 a.m., and took two 200 microgram pills of Cytotec. Within 15 to 20 minutes menstrual-like cramps kicked in. Some women feel nauseous. A few vomit. The women go to the toilet often, and eventually expel the egg into a steel bed pan. Expulsion should take place within three hours.

“I was waiting for it. Waiting, waiting, waiting for it,” recalls Monica, growing more anxious as talks. She's a pretty woman, small and delicate, with soft cinnamon-colored hair cut in a swishy French bob and almost-translucent freckles across her face to match. On her left hand is a simple gold band, on her body a plain black crew neck and well-worn jeans. She waves her hands around as she talks, her nails unpolished and cut very short.

Finally, she says with a sigh, she was examined, because she was 20 minutes past the three-hour deadline. "The doctor started pushing on my stomach. It's really like giving birth," she says. “There I was with my legs up and the doctor was pushing, pushing, pushing, and then she says, ‘Oh, what a beautiful egg. Do you want to see it?’”

Each woman who undergoes an RU-486 abortion is invited to see her “abortion product”—an inch-long lump of bloody membrane about the thickness of your little finger. This, say the women, is what affects them the most.

“I think, you know, sitting on the toilet and seeing it, you’re not going to forget it,” says Nadia, the American student. “Having those pains, you're not going to forget it.”

“Some say they would have rather have had aspiration because they wouldn't have liked to see the abortion product,” says nurse Christiane Andreassian, adding that when it's older, “they see the embryo.”

Nadia sits down with Andreassian to discuss her post-abortion regimen. She is given some pain relievers, anti-clot medicine and a pack of birth control pills which she is told to start using on Sunday. This is to re-regulate her menstrual cycle.

Then the nurse hands her a form which she must use to record each evening the level of bleeding she has experienced that day (bleeding generally lasts 8 to 10 days). On the reverse side, she is asked to write her thoughts about the experience.

And what do the women write?

They would have rather not known what was going on, says Andreassian. It takes too long, reports Aubeny. But in general, says Andreassian, the women are satisfied with the procedure, mainly because “you take the pills yourself. You do everything yourself."

There are times—about once a week—when the women don’t take the pills. “Oh, I could write a book on that!” laughs Andreassian. They throw the pills on the floor. They cry. They say they can’t do it, even though they’ve gone to the gynecologist, reflected for eight days, and met with the social worker. At the last minute, they back out.

On a recent day, Andreassian had a patient who had gone through all the steps and was there to take the RU-486. But she couldn’t. “She was really disturbed,” Andreassian says. “And I said, ‘I not going to push you to take those pills.’” Andreassian calculated the last day the patient could take the pills under the government-set deadline. “I said, ‘Go back home, reflect on that, discuss with your friend, because you are too troubled today.’ When the women are troubled we can’t give the RU. We won’t give them the RU. We just postpone. And if it’s too late for the RU, there’s still time to do aspiration.”

Women in France can take RU-486 until the 49th day of their pregnancy, but can undergo aspiration up to the tenth week. The government is expected to extend the deadline for RU-486 abortions to 63 days very soon. Dr. Grimes notes, though, that the effectiveness of RU-486 “tapers off” after seven weeks.

Two days later, Andreassian’s patient came back and took the RU-486 pills.

Someday, probably before the end of the century, women won’t have to use RU-486 to abort a fertilized egg. They will be able to take the compound as a less-extreme version of the morning-after pill prescribed by some doctors in the United States to block the implantation of the egg. Two studies for this use have already been conducted by the World Health Organization's Human Reproduction Program.

In the tests, none of the women had an implanted pregnancy, and unlike the current estrogen-based morning-after pill which causes extreme nausea and sometimes vomiting, there were no side effects with RU-486, says program associate director Paul Van Look. In another trial, out of 157 women, only one became pregnant, reports Baulieu. Van Look believes this could be available within two to three years.

A similar non-abortion/non-pregnancy use for the compound is as a once-a-month pill, to induce menstruation. In one study, four percent of the women remained pregnant. Baulieu believes that this could become more efficient when combined with Cytotec.

And studies are currently being conducted on the possibilities of taking RU-486 as a daily oral contraceptive. There are two basic approaches, explains Van Look. One is like the mini-pill, which does not disturb the menstrual cycle but blocks the implantation of the egg. The second, he says, suppresses ovulation, like the current birth control pill. For ovulation-suppression, the dosage of RU-486 would need to be higher and combined with progesterone at the end of the cycle.

The theoretical advantages of RU-486 over an estrogen-based daily oral contraceptive, says Van Look, are the possible elimination of “some of the more unpleasant complications such as cardiovascular problems, and general side effects, such as headaches, which seem to related to estrogen.”

Baulieu further theorizes that if RU-486 can suppress ovulation, perhaps it can be used for the treatment of endometriosis, fibroids and human papilloma virus.

According to Baulieu, RU-486, combined with a prostaglandin, could be used for therapeutic second and third trimester abortions. The benefits of this procedure versus aspiration are the reduction of pain and accelerated expulsion. RU-486, given in two doses of 200 mg, has been tested on women at term to induce labor. Spontaneous deliveries were significantly increased and the time to induce labor was shortened. More importantly, there appear to be no adverse effects on either the mother or the infant. Baulieu says he hopes this will cut down the number of Caesarian sections.

Meningiomas, common tumors which are usually benign yet can impair the brain functions or cause death if not surgically removed, have responded well to treatment with RU-486, sometimes stopping growth. In 1992, the FDA allowed the importation of RU-486 for experimental use on a man with inoperable brain cancer.

Tests are currently being conducted on local use of RU-486, or its derivatives, for treating glaucoma and to accelerate or amplify wound and healing, particularly in stressed and/or aging patients.

Large doses of RU-486 has been used successfully in treating Cushing’s Syndrome, a disease caused by cancer in the adrenal glands or adrenal-related organs. RU-486 counters the affects and makes it possible for tumors to be removed.

And for breast cancer treatment, RU-486 inhibits the growth of cancer cells. In a test with women who have advanced metastatic breast cancers, who often don't respond to the antiestrogen tamoxifen, 25 percent reacted very positively to RU-486. Two more trials are currently being conducted: in France, with women with metastatic cancer who are tamoxifen-resistant, and in Canada with women with metastatic cancer who are not known to be tamoxifen-resistant. Results will be known by year-end.

When the Population Council begins its testing in the United States this year for eventual FDA approval, it will have the benefit of the years of research, testing and practical application of RU-486. The Council believes it will not take very long complete its required 2,000 abortions with the compound since there are about 1.6 million abortions in the United States every year.

What will take time is preparing the New Drug Application for the FDA. All the data related to RU-486 must be assembled. Norplant’s NDA ran approximately 100,000 pages long, and had to be transported in a truck, which, an FDA spokesman says, is not all that unusual.

Once received, the FDA confirms all the data, often visiting the research sites. “Then the U.S. experience will be folded in,” Waldman says, “and we’ll had to include a name of a manufacturer.”

She says that more than 20 small pharmaceutical companies have expressed interest in producing the compound, and points out that big corporations do not need neither the money nor the negative publicity that the politically combustible product would bring. Roussel-Uclaf president Edouard Sakiz even declared that no big company would touch RU-486.

Roussel-Uclaf will to transfer the technology to the U.S. manufacturer, which will in turn have to prove to the FDA that the pills are exactly the same as those produced in France.

“It’s a tricky business,” says Waldman. “It’s not easy and it’s not that pleasant but it’s something that's necessary. That's what it's all about.”

Whether the final approval takes two years or five, what seems most important now is that the debate over RU-486 has finally moved away from political to the medical effects of this drug, which many say is where efforts should have been along.

And if RU-486 doesn\ t work out? “There are over 400 anti-progesterone out there,” says Grimes, noting that Schering AG of Berlin, Germany, has developed two, onapristone and lilopristone, which have already been extensively tested on animals. “RU-486 is the first but by no means the last.”

Says Aubeny, “We have the greatest hopes for this medicine.”

Style Files Shop

Don’t forget to check out Style Files recommendations of all sorts of things, from items, decor, books, and films mentioned in this newsletter to sustainable fashion and beauty products I love.

If you’d like to engage me as a speaker for a conference or event, drop a line.

To keep up with my work:

Follow me on Instagram

Buy my books:

Listen to my award-winning podcast, The Green Dream, on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

The Style Files may earn a small commission if you shop via affiliate links in this newsletter.

😳